Pierfishing

Lobsterilla — A Giant Lobster From The Oceanside Pier

Persevering twins reap late reward of one giant lobster

Persevering twins reap late reward of one giant lobster

One of the very best writers that I know from my time in the “Outdoor Writers Association of California” is San Diego’s Ed Zieralski. Here’s a story he wrote about a little lobster.

By Ed Zieralski, San Diego Union-Tribune, October 20, 2002

It was another marathon Saturday with dad, starting with a 6:30 a.m. tee time and finishing at midnight at the Oceanside Pier.

But it turned into a very special day for Blake and Garett Spencer, a pair of 9-year-old twins who teamed with their father, Todd, to catch a lobster of a lifetime.

“Saturday is my day with the boys, and we started with 18 holes at Temeku (Golf Course),” said Escondido’s Todd Spencer, manager of a collection agency.

From there, it was on to Oceanside Pier for some hoop-netting for lobsters, an activity the boys later told their dad they’d pick over playing video games.

“This was only our second time hoop-netting,” Spencer said. “We went at the end of last season and fished off Ocean Beach Pier. We didn’t get anything, but the boys loved it.”

Last Friday, the boys asked their father: “When are we going lobster hunting again?”

Spencer promised they’d go after his golf outing the next day. They packed their rig with items that don’t necessarily go together like ham and eggs: dad’s golf bag and gear, a couple of hoopnets and 21/2 pounds of mackerel for lobster bait.

Golf and hoop-netting, an outdoorsman’s daily double, for sure.

Golfing done, Spencer said they arrived at the Oceanside Pier at 6 p.m. and started fishing the windward side of the pier.

“We were the only ones with hoopnets, and I was beginning to think the Oceanside Pier wasn’t the right place to hoop-net for lobsters,” Spencer said.

He turned to his boys after a few hours of not getting anything and asked them, “Would you guys rather be home with your new X-Box games, or would you rather be out here on the pier fishing and not catching anything?”

They chose being on the pier over playing video games. This was more fun, and besides, it was quality time outside with dad.

“That made me feel pretty good,” Spencer said. “I’m from Northern California. I grew up in the foothills of Yosemite, out in the country. My kids are city kids, but they have the same interests I have. They love being outdoors.”

Shortly after their talk, Spencer switched to the leeward side of the pier, and the change produced two short lobsters, each about 1/4-inch short, just after 10 p.m. They sent them back like good sportsmen.

Another pick of the net produced a giant spider crab, about a 6- or 7-pounder, Spencer said. He was about to throw it back, but a man told him to keep it because it was very good eating.

“It looked nasty, but he said it was good,” Spencer said. “I cooked it later, and it not only looked nasty, it tasted nasty. Next time, it’s going back into the water.”

The spider crab provided a thrill to Spencer and his boys, and since it was getting close to midnight, Spencer felt it was time to go.

But then Spencer heard the cry of, “C’mon dad, one more pull, one more pull before we go.” “One more pull” to a hoop-netter is what “one more cast” is to a fisherman, what “one more shot” is to a bird hunter.

Spencer gave in. They made a set, left it for a while and made one more pull.

“It was the last pull of the night,” Spencer said.

And what a pull.

As the net came up, Spencer and his boys couldn’t believe their eyes. There in the net was what Spencer later called the “mutant lobster.” He never weighed the giant crustacean, but, including its antennae, the giant bug was at least 46 inches long, nearly as tall as his boys, who are 56 inches tall. He estimated it at 15 pounds.

California spiny lobsters have been known to go as high as 25 to 30 pounds. Biologists figure a lobster that big could be anywhere from 50 to 150 years old.

“I have a friend who dives, and he’s saying it’s a minimum of 15 pounds,” Spencer said. “I wish now I would have taken it to a supermarket or somewhere and weighed it,”

Spencer and his boys celebrated the next day with a lobster feast.

“You know how people say the big old lobsters are tough and not good eating,” Spencer said. “That’s not so. This lobster was tender and sweet. Really god eating.”

Looking back, Spencer said he likely would have quite around 9 p.m. had the boys chosen to go home to play video games.

“It was all because they wanted to stay,” Spencer said. “It was our day out. And what a fantastic day.”

California Yellowtail —

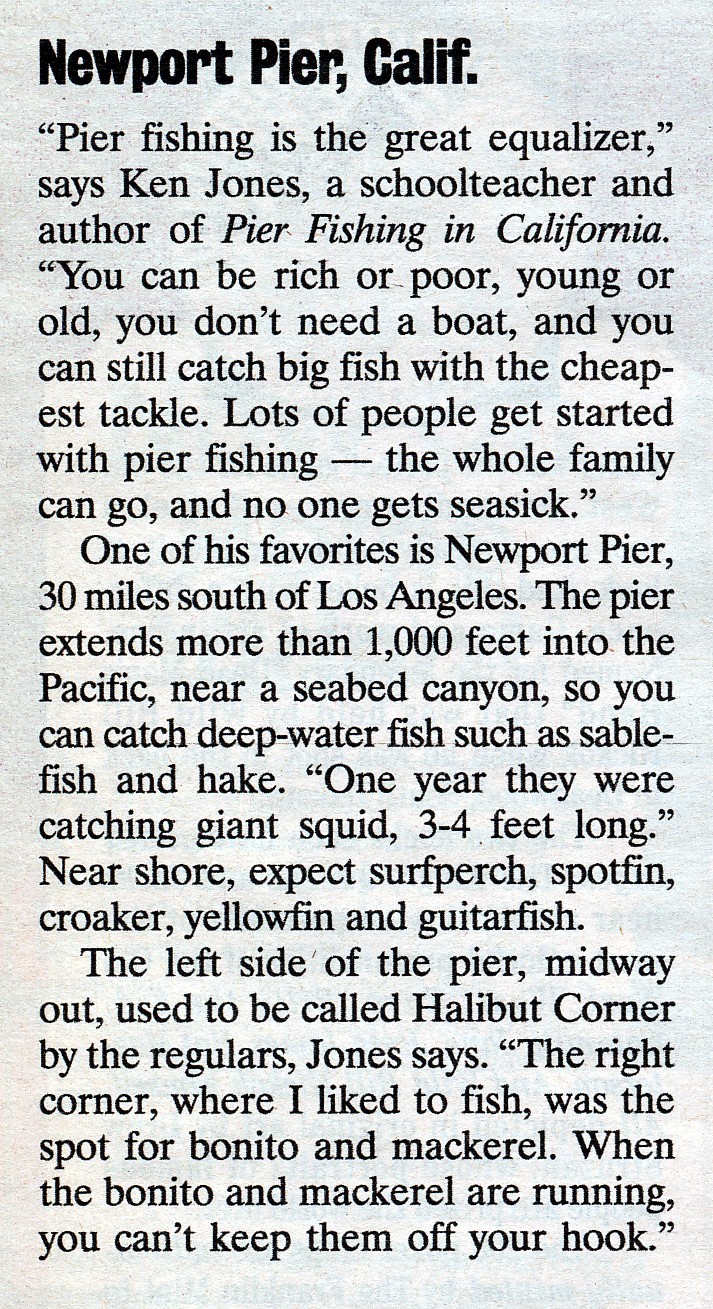

Yellowtail caught at the Crystal Pier in San Diego by Angel Hernandez in September 2015

Yellowtail caught at the Crystal Pier in San Diego by Angel Hernandez in September 2015

35-Pound yellowtail taken from the Balboa Pier by “Aaron”on November 1, 2003

35-Pound yellowtail taken from the Balboa Pier by “Aaron”on November 1, 2003

Species: Seriola dorsalis (Valenciennes, 1833); from the Italian word seriola (for amberjack) and dorsalis (the long dorsal fin). Some sources now use Seriola lalandi.

Alternate Names: Yellowtail, amberjack, white salmon, amber fish, forktail, tails, rats (little fish), firecracker (small fish), mossback (large fish) and cavasina. In Mexico typically called esmedregal or medregal de rabo amarillo.

Yellowtail from Crystal Pier, August 2016

Yellowtail from Crystal Pier, August 2016

Identification: Typical jack shape with metallic blue to green above, a brassy horizontal band along the sides from eye to tail; silvery below; some fish are olive-brown to brown. Fins and tail are yellowish

Yellowtail caught at Crystal Pier on September 21, 2006 by Montre Somsukcharean; reported at 55 pounds. (Photo courtesy of Peggi Straker)

Yellowtail caught at Crystal Pier on September 21, 2006 by Montre Somsukcharean; reported at 55 pounds. (Photo courtesy of Peggi Straker)

Size: To 80 pounds and over 5 feet long. Most caught from piers are less than 10 pounds, the small fish called “rats” or “firecrackers.” The California record fish weighed 63 lb 1 oz and was caught at Santa Barbara Island in 2000.

Range: Circumglobal in warmer waters and some temperate waters. In the eastern Pacific from Chile to northern British Columbia. Unverified reports from Gulf of Alaska off Kodiak Island and Cordova. Uncommon north of Point Conception.

48.5-pound yellowtail caught at the Crystal Pier in August 2012 by Tony Troncale

48.5-pound yellowtail caught at the Crystal Pier in August 2012 by Tony Troncale

Habitat: Usually found around offshore islands, rocky reefs, or kelp beds. Primarily feeds on squid and fish.

40 Pound yellowtail taken by Angel Hernandez at the Crystal Pier on June 14, 2017

40 Pound yellowtail taken by Angel Hernandez at the Crystal Pier on June 14, 2017

Piers: Most southern California piers located near reefs or kelp will see a few yellowtail caught during the year. However, they are always a bonus fish and rarely caught in large numbers off of piers. Best bets: Ocean Beach Pier, Crystal, Oceanside Pier, San Clemente Pier, Redondo Beach Pier, and the Hermosa Beach Pier. Cryastal Pier in San Diego is by far the best pier in the state for yellowtail and many fish in the 30-50 pound range have been taken.

42-pound yellowtail caught at Crystal Pier— October 2004

42-pound yellowtail caught at Crystal Pier— October 2004

Shoreline: Rarely taken by shore anglers.

Boats: One of the most prized species for boaters in southern California. The traditional “yellowtail grounds” have been at Catalina and the Coronado Islands.

34-Pound yellowtail caught at Crystal Pier in August of 2012 by “Hallman”

34-Pound yellowtail caught at Crystal Pier in August of 2012 by “Hallman”

Bait and Tackle: If an angler wants to try for yellowtail he should have heavy enough tackle to insure a fair chance of landing the fish. Yellowtail like to head for rocks or kelp as soon as they’re hooked so line should test 20-30 pounds, hooks should be small (size 6 or 4) but strong, and the angler must make sure the fish is played out before it nears the pier and the pilings. Although lures work well on boats, almost all of the pier-caught yellowtail are taken on live bait—especially on small jack mackerel, Pacific mackerel or Pacific sardines.

A small “firecracker-size” yellowtail taken from the Redondo Sportfishing Pier in 2011

A small “firecracker-size” yellowtail taken from the Redondo Sportfishing Pier in 2011

Food Value: A fairly good tasting fish that is usually broiled or bar-b-cued.

34 Pound Yellowtail caught by Angel Hernandez at Crystal Pier, August 2016

34 Pound Yellowtail caught by Angel Hernandez at Crystal Pier, August 2016

Comments: One of the favorite southern California sport fish but much more common out in deeper water.

What remains of a 54″, guesstimated 40-pound yellowtail that was hooked and then hit by a sea lion at the Redondo Beach Pier in October 2008

What remains of a 54″, guesstimated 40-pound yellowtail that was hooked and then hit by a sea lion at the Redondo Beach Pier in October 2008

Yellowtail taken at the Manhattan Beach Pier in 2012

Yellowtail taken at the Manhattan Beach Pier in 2012

46-Pound yellowtail taken at the Crystal Pier by Thomas Shinsato in August 2015

46-Pound yellowtail taken at the Crystal Pier by Thomas Shinsato in August 2015

A small “rat-sized” yellowtail caught by Rita Magdamo during the James Liu Memorial Derby at the Cabrillo Mole in Avalon in September 2014

Another small “rat-sized” yellowtail caught in Avalon. The fish was caught at the Green Pleasure Pier in September 2014 although the picture is at the Cabrillo Mole.

Another small “rat-sized” yellowtail caught in Avalon. The fish was caught at the Green Pleasure Pier in September 2014 although the picture is at the Cabrillo Mole.

A pretty-colored yellowtail taken at the Crystal Pier in August 2016

A pretty-colored yellowtail taken at the Crystal Pier in August 2016

Tony Troncale’s 48.5-pound yellowtail from Crystal Pier, August 2012

Tony Troncale’s 48.5-pound yellowtail from Crystal Pier, August 2012

Hard to believe, but a yellowtail taken from Monterey’s Wharf #2 in 2012.

Hard to believe, but a yellowtail taken from Monterey’s Wharf #2 in 2012.

36-Pound yellowtail caught at Crystal Pier in August 2016 by Studman

36-Pound yellowtail caught at Crystal Pier in August 2016 by Studman

53.46-pound yellowtail taken by Big Angel at the Crystal Pier in August 2019

Yellowtail taken by Angel at the Crystal Pier in August 2019

Yellowtail taken by Angel at the Crystal Pier in August 2019

53.46-pound yellowtail taken by Angel at the Crystal Pier in August 2019

My very first yellowtail. Taken in San Diego many, many years ago.

My very first yellowtail. Taken in San Diego many, many years ago.

Aaron leaving the Balboa Pier with a 35-pound yellowtail in 2003

Aaron leaving the Balboa Pier with a 35-pound yellowtail in 2003

Some large yellowtai caught from piers

55 Lbs. — Crystal Pier (San Diego), Montre Somsukcharean, September 21, 2006—Source: Source: James Barrick, Crystal Pier Bait Shop & Peggi Straker

53.46 Lbs. — Crystal Pier (San Diego), Angel, August 12, 2019—Source Pam, Crystal Pier Bait Shop

52 ½ Lbs. — Pine Ave. Pier (Long Beach), D. W. Fletcher, September 19, 1896—Source: Los Angeles Herald, September 19, 1896

50 Lbs. — Pine Ave. Pier (Long Beach), Al Decker, July 1894—Source: Los Angeles Herald, July 3, 1894

48.5 Lbs. — Crystal Pier (San Diego), Tony Troncale, August 6, 2012—Source: James Barrick, Crystal Pier Bait Shop & Tony Troncale

46 Lbs. — Crystal Pier (San Diego), Thomas Shinsato, August 2015—Source: Source: Crystal Pier Bait Shop & Thomas Shinsato

42 Lb. 1 oz. — Oceanside Pier, Elmo Nealoff, July 1955—Source: Oceanside Pier Bait Shop

42 Lbs. — Crystal Pier (San Diego), October 2004—Source: James Barrick, Crystal Pier Bait Shop

40 Lb. — Crystal Pier (San Diego), Angel Hernandez, June 14, 1917 — Source: Personal communication

≈ 40 Lbs. — Redondo Beach Pier, October 2008 — Source: bloodydecks.com

40 Lbs. — Avalon wharf, W. M. LeFavor, May 21, 1908—Source: Los Angeles Herald, May 22, 1908

40 Lbs. — Wharf No. 3, Redondo Beach, Japanese fisherman, August 1907—Source: Los Angeles Times, August 18, 1907

40 Lbs. — Avalon wharf, Mrs. Boyce, June 9, 1897—Source: Los Angeles Herald, June 10, 1897

≈ 40 Lbs. — Redondo Beach Pier, October 2008—Source: bloodydecks.com

≈ 40 Lbs. — Hotel del Coronado Pier, September 21, 1899—Source: Los Angeles Times, September 22, 1899

40 Lbs. — Wharf No. 1 (Redondo Beach), Seth Owens, August 22, 1897 — Source: Los Angeles Herald, August 22, 1897

40 Lbs. — Avalon wharf, Mrs. Boyce, June 9, 1897 — Source: Los Angeles Herald, June 10, 1897

36 Lbs. — Crystal Pier (San Diego), August 2016—Source: Crystal Pier Bait Shop

35 Lbs. — Crystal Pier (San Diego), August 2012—Source: James Barrick, Crystal Pier Bait Shop

35 Lbs. — Balboa Pier, Aaron, November 1, 2003—Source: PFIC

34 Lbs. — Crystal Pier (San Diego), Hallman, August 2012 —Source: James Barrick, Crystal Pier Bait Shop

34 Lbs. — Crystal Pier (San Diego), Angel Hernandez, August 2016—Source: Angel Hernandez

34 Lbs. — Wharf No. 3 (Redondo Beach), William Codie, September 26, 1910 — Source: The Redondo Reflex, September 29, 1910

34 Lbs. — Avalon Wharf, Al Delaney, August 17, 1908 — Source: Los Angeles Times, August 16, 1908

33 ½ Lbs. — Wharf #3 (Redondo Beach), August 24, 1910—Source: Santa Ana Register, August 25, 1910

33 Lbs. — Newport Wharf, E. P. Deffley, May 1909—Source: Los Angeles Herald, May 22, 1909

32 ½ Lbs. — Redondo Wharf, August 23, 1891—Source: Los Angeles Herald, August 24, 1891

32 ½ Lbs. — Avalon Wharf, W. M. LeFavor, May 20, 1908—Source: Los Angeles Herald, May 22, 1908

30 Lbs. — Huntington Beach Pier, Earl Nelson, May 7, 1934—Source: Santa Ana Register, May 8, 1934

30 Lbs.— Hotel del Coronado Pier, Joe Larnel, August 31, 1898—Source: Los Angeles Times, September 1, 1898

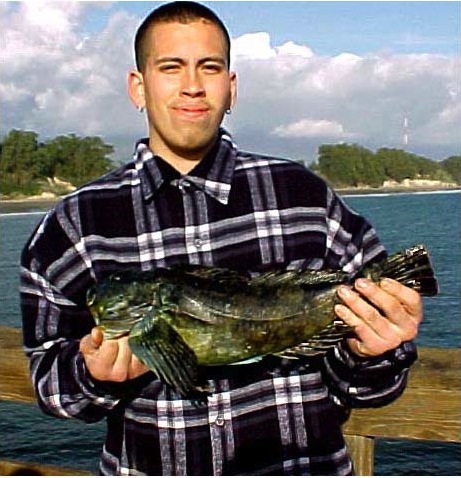

Cabezon — King of the Sculpin

A nice cabezon from the Redondo Sportfishing Pier

Species: Scorpaenichthys marmoratus (Ayres, 1854); from the Greek words scorpaena (a related species) and ichthys (fish), and the Latin word marmoratus (marbled).

Great picture of a cabezon caught from the rocks in Mendocino County by FireRidge in 2016

Great picture of a cabezon caught from the rocks in Mendocino County by FireRidge in 2016

Alternate Names: Commonly called bullhead; also marbled sculpin, cab, cabby, bull cod, blue cod, giant sculpin, giant marbled sculpin, scorpion, marble sculpin, salpa and scaleless sculpin. Called scorpion or biggy-head by 19th century Italian fishermen.

A cabezon at the Trinidad Pier

A cabezon at the Trinidad Pier

Identification: Cabezon have a very large head with a broad bony support from the eye across the cheek, no scales, a cirrus (fleshy flap) on the midline of the snout, and a pair of longer cirrus just behind the eyes. The coloring is brown, bronze, reddish, or greenish above, whitish or turquoise green below, with dark and light mottling on the side. The lining of the mouth is a translucent turquoise green. The color may correlate to their sex with 90% or greater red-colored cabezon being males, 90% or greater green-colored cabezon being females. The mouth is broad with many small teeth.

A cabezon from the Goleta Pier

A cabezon from the Goleta Pier

Size: To 39 inches and 25 pounds; most caught from piers are less than two feet. The California record cabezon was a fish weighing 23 lb 4 oz; it was taken near Los Angeles in 1958. The cabezon is the largest member of the cottid (sculpin) family.

Up close and personal with a cabezon’s head — picture taken by ChemFish in 2014

Up close and personal with a cabezon’s head — picture taken by ChemFish in 2014

Range: Punta Abreojos, central Baja California, to Samsing Cove, near Sitka in southeastern Alaska.

Habitat: Typically found in shallow-water rocky areas, from intertidal pools to jetties, kelp beds and rocky reefs, any area with dense algal growth. Older fish tend to move to deeper water, as deep as 250 feet. Typically inhabits the tops of rocky ledges as contrasted with rockfish and lingcod that prefer the sheer faces of ledges. Cabezon like to sit and it doesn’t seem to matter if it’s in a hole, on the reef, or on vegetation, they sit versus actively swimming.

A cabezon taken from the Cabrillo Mole in Avalon on Catalina Island in 2012

A cabezon taken from the Cabrillo Mole in Avalon on Catalina Island in 2012

Piers: Cabezon are one of the premier fish for northern California pier anglers with lesser numbers taken from southern and central California piers. Best bets: Cabrillo Pier, Goleta Pier, Monterey Coast Guard Pier, Santa Cruz Pier, San Francisco Municipal Pier, Point Arena Pier, Trinidad Pier and Citizens Dock (Crescent City).

A cabezon from the Elephant Rock Pier in Tirburon

A cabezon from the Elephant Rock Pier in Tirburon

Shoreline: A favorite catch for rocky shore anglers throughout California. A small cabezon from the Elephant Rock Pier

A small cabezon from the Elephant Rock Pier

Boats: A prize species for boaters in central and northern California.

Another small cabezon from the Elephant Rock Pier

Another small cabezon from the Elephant Rock Pier

Bait and Tackle: Although most of the cabezon caught from piers will be fairly small fish less than two feet in length, most years also see some larger fish in the 8-12 pound category. Because of this, you should use at least medium sized tackle; line testing at least 15 pound breaking strength and hooks around 2/0 in size. The best baits are small crabs and fresh mussels but cabezon will bite almost anything that looks like food. Their normal diet includes crabs, small lobsters, abalone, squid, octopus, small fish and fish eggs. Although they often reach good size, they can be frustrating to catch. Cabezon will often tap or mouth bait and spit it out; patience and a feel for when to set the hook is required. Also remember that cabezon like to congregate around “cabezon” holes; if you catch one, there will often be more around.

A Monterey Cabezon from the Coast Guard Pier

A Monterey Cabezon from the Coast Guard Pier

Food Value: Excellent mild-flavored meat that can be prepared in almost any manner; many feel it is best fried. Although few fish are better eating, anglers should not eat the roe (eggs) of cabezon—the eggs are poisonous and can make a person violently ill. Don’t worry if the flesh is blue colored, this is a common occurrence and the flesh will turn white when cooked.

A cabezon from the Point Arena Pier — 1988

A cabezon from the Point Arena Pier — 1988

Comments: A “lie-in-wait” predator. Their coloring lets them blend in with the surroundings where they lie motionless. When food passes by they use their large, powerful pectoral fins and tails to lunge after the prey engulfing it in their large mouths. In Spanish, cabezon means big headed or stubborn and it well describes both their looks and temperment. Cabezon can live to about 20 years of age and I imagine an old cabezon would be a real grouch.

A cabezon caught by “Dwight” at Citizens Dock in Crescent City in 2013

A cabezon caught by “Dwight” at Citizens Dock in Crescent City in 2013

A beautiful red-colored cabezon (Picture courtesy of makairae)

A beautiful red-colored cabezon (Picture courtesy of makairae)

A SoCal cabezon caught at the Santa Monica Pier

A SoCal cabezon caught at the Santa Monica Pier

A Point Arena Pier cabezon caught by Dan

Cabezon taken at the Point Arena Pier by calrat in 2003

A cabezon caught by norcal at the Pillar Point Pier in 2012

A cabezon taken at the Stillwater Cove Pier by Freeman in 2010

A cabezon taken at the Stillwater Cove Pier by Freeman in 2010

A cabezon from the Ocean Beach Pier in San Diego in 2010

A cabezon from the Ocean Beach Pier in San Diego in 2010

A “baby” cabezon, this one from Citizens Dock in Crescent City in 2015

A “baby” cabezon, this one from Citizens Dock in Crescent City in 2015

A juvenile cabezon, this one a product of the small pier at Brookings Harbor, Oregon

A juvenile cabezon, this one a product of the small pier at Brookings Harbor, Oregon

And the winner in the smallest fish category — a cabezon taken at the Del Norte Street Pier in Eureka by qchris87

And the winner in the smallest fish category — a cabezon taken at the Del Norte Street Pier in Eureka by qchris87

A cabezon caught at the Trinidad Pier Kids Derby in 2013

A cabezon caught at the Trinidad Pier Kids Derby in 2013

Another cabezon caught at the Trinidad Pier Kids Derby in 2013

Another cabezon caught at the Trinidad Pier Kids Derby in 2013

A cabezon caught at the Trinidad Pier Kids Derby in 2014

A cabezon caught at the Trinidad Pier Kids Derby in 2014

Oceanside Businessman Pulled from Pier —

Angler Fails To Land Fish — Large Catch Wins in Fight For Freedom — Rescuers Save Fisherman from Drowning

Oceanside, July 17—When a big fish, hooked off the end of the Oceanside pier about 6:30 o’clock last evening, decided he did not like fishermen and did not want to leave his happy home in the waters of the Pacific, he came very near making one less fisherman instead of one less fish.

C.A.Peddicord, Oceanside businessman, intent upon catching a large fish, bought brand-new fishing tackle, baited the hook with a pound and a half mackerel, and proceeded to wait. He caught it all right, but the fish objected to being taken from the water and proceeded to throw Peddicord over the railing of the pier, break his leg, land him in the deep water, and leave him to flounder desperately to keep afloat until he was saved by Cal Young coming to his rescue in a skiff and getting him aboard. Just before the skiff arrived to avert a drowning tragedy, Jim Donnell, popular high school graduate of this year, made a quick dash for a life preserver near by and threw it to the struggling man. He could not reach it, however, but the appearance of a man below the pier encouraged the drowning man just enough that he continued to fight to keep above water until he was rescued.

Peddicord had fished more or less for years, but had never caught a big fish. He got the heavy tackle with the intention of getting the thrill of the big-fish catch. As he waited for the fish to bite, he received instructions about how to set his drag, not too heavy, he was told, and learned how to hold the rod. He waited and waited but the fish seemed unconcerned so he tightened up his drag a few turns and thought it would be easier to slip the pole under his leg and be ready for business if any surprise came. The surprise arrived and he proceeded to reel in his fish and had it fairly up to the pier when it made a dart underneath. He leaned over to see what was happening down there when the fish gave a big lurch and Peddicord made a flip over the rail, the pole acting as a lever, the fish on the long end, he on the short. As he went over he grabbed for support, struck his leg on the cross beam of the pier, breaking his leg halfway between the ankle and the knee.

Just what kind of a fish it was that he caught is unknown. He had a regular jewfish outfit, but it is believed not to have been a jewfish that put on this surprise exhibition of fish ingenuity and activity.

Los Angeles Times, July 18, 1930

Great Whites & Makos —

Stories like the following seem to crop up every few years, especially at piers in Santa Monica Bay such as Hermosa Beach Pier and the Manhattan Beach Pier. Great whites are illegal, makos are legal, and too many fisherman don’t make the effort to learn the differences.

Great white shark isn’t a great catch

By Ed Zieralski, San Diego Union-Tribune, June 10, 2003

A Los Angeles fisherman who caught a 1-to 2-year-old great white shark from the Hermosa Pier will be cited by the State Department of Fish and Game for killing a protected species.

Abraham Ulloa, a general contractor from Los Angeles, posed with the estimated 61/2 -foot white shark on the pier June 7 along with two Hermosa Beach lifeguards.The photo appeared with a story in the Easy Reader, a Hermosa Beach newspaper, and even though the caption identified the catch as a “200-pound mako,” the story and headline identified it as a “great white shark.”

The story described Ulloa’s two-hour battle with the shark on 40-pound test line and heavier leader and how two fishing buddies helped haul the fish up with grappling gaffs.

Outraged by the story and photo, sport and commercial fishermen called Fish and Game officials and media. Many criticized the Hermosa Beach lifeguards for their involvement.” We received a lot of tips from the public on this,” said Carrie Wilson, a marine biologist with the DFG. Lauren Gangle,notified her supervisors at California DFG. She works as a Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission regional supervisor and is graduate student in marine biology. Mrs. Gangle collects data from commercial fisherman without their fear of any report of mismanagement. Ms. Gangl was present in Hermosa Beach at time of the capture of the Great White and contacted Ms. Wilson to report data. “Lauren gave me data and then I decided to proceed with violation proceedings.”

Department of Fish and Game warden Rebecca Hartman investigated and traced Ulloa to his home in Los Angeles. Ulloa told her his family had eaten some of the fish, and he had distributed portions to friends. But he still had the fins and jaws of the shark. Hartman didn’t cite Ulloa because he claimed he thought it was a mako shark. She confiscated the fins and jaws and took them to a marine biologist for identification.”At that young age, the teeth are somewhat like a mako’s, but the great white has serrated bottom teeth,” Lowe said. “And its uppers are more triangular than a mako’s.”

Hartman plans to cite Ulloa even though he professed ignorance. “It’s a violation even though he claims he didn’t know what it was,” Hartman said. “The law is set up to protect the animal. If you don’t know what it is, don’t take it. In this case, this individual took a great white shark, a predator that keeps sea lions in check and fills a certain niche in the ocean.”

Ulloa could not be reached for comment. He faces a misdemeanor charge, a fine of $1,000 and/or six months in county jail. Hartman said the Hermosa Beach lifeguards in the picture with Ulloa won’t be charged because they arrived after the shark was killed. They played no role in the killing of the fish, she said. Lifeguards Charlie Piccaro and Bill “Shark” Harkins’ only “crime” is they posed with Ulloa over a dead protected great white shark.

Lowe said Southern California is a nursery for great whites, and he estimates six to eight young great whites are caught each year by sport and commercial fishermen between Dana Point and Ventura.*** He said it’s important that laws stay in place to protect them. “The best guess is that great white sharks take 12 to 18 years to mature and give birth,” he said. “And when they do give birth, it’s only to one or two pups at a time. These fish have a life span of humans.” *** I think the number has gone up since then.

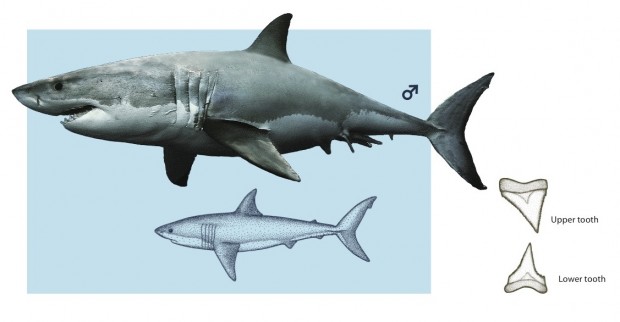

•••••••••••••••••••• Great White Shark ••••••••••••••••••••

Species: Carcharodon carcharias (Linnaeus, 1758); from the Greek carcharodon (rough and tooth), and carcharias (the ancient Greek name for the species). Class Chondrichthyes, Subclass Elasmobranchii, Superorder Galea, Order Lamniformes, Family Lamnidae—Mackerel sharks.

Species: Carcharodon carcharias (Linnaeus, 1758); from the Greek carcharodon (rough and tooth), and carcharias (the ancient Greek name for the species). Class Chondrichthyes, Subclass Elasmobranchii, Superorder Galea, Order Lamniformes, Family Lamnidae—Mackerel sharks.

Alternate Names: It has many names throughout the world. Most common are great white and man-eater. Others include great white death, white pointer, Mango-ururoa (New Zealand), and Grand requin blanc (France). Called Tiburón blanco in Mexico.

Identification: Large, powerful body with the 1st dorsal fin over rear of of pectoral fin; 2nd dorsal fin begins in front of anal fin. Dark metallic-gray, slate-blue, brownish or blackish above, lighter on side, white below. Sometimes has a black spot at the base of the pectoral fin or on the underside of the pectoral fin near the tip. The teeth are very large and triangular, with serrated, saw-tooth edges.

Identification: Large, powerful body with the 1st dorsal fin over rear of of pectoral fin; 2nd dorsal fin begins in front of anal fin. Dark metallic-gray, slate-blue, brownish or blackish above, lighter on side, white below. Sometimes has a black spot at the base of the pectoral fin or on the underside of the pectoral fin near the tip. The teeth are very large and triangular, with serrated, saw-tooth edges.

Size: Although reported to 36 feet, and over 4,000 pounds in weight, most are under 21 feet in length. In California reported to nearly 20 feet in length.

Size: Although reported to 36 feet, and over 4,000 pounds in weight, most are under 21 feet in length. In California reported to nearly 20 feet in length.

Range: From Gulf of California to Gulf of Alaska.

Habitat: Inshore and offshore areas, especially near seal or sea lion rookeries.

Piers: White sharks have been taken at several piers including those at Manhattan Beach, Hermosa Beach, Huntington Beach and Goleta. A great white was reported hooked and lost at the Pacifica Pier in 1991. Almost all were young pups under six feet in length although the one that decided to visit Pacifica grabbed a hooked salmon of ten pounds or so and was estimated at 12 feet in length and 700 pounds. The carcass of a small, four-foot-long baby white floated by the Point Arena Pier in March of 1997 until grabbed by a couple of the local local youth.

Bait and Tackle: None, illegal to take

Food Value: None, illegal to take.

Comments: Among the swimmers killed by great whites in California was one who decided to swim with the sea lions next to the Avila Beach Pier. It was a bad idea.

Comments: Among the swimmers killed by great whites in California was one who decided to swim with the sea lions next to the Avila Beach Pier. It was a bad idea.

Great quote by Quint in “Jaws” — Sometimes that shark, he looks right into ya, right into your eyes. Y’know, the thing about a shark, he’s got lifeless eyes, black eyes, like a doll’s eyes. When he comes after ya, he doesn’t seem to be livin’ until he bites ya, and those black eyes roll over white, and then – aww, then you hear that terrible high-pitch screamin’, the ocean turns red, and in spite of all the poundin’ and the hollerin’, they all come in and rip ya to pieces…

•••••••••••••••••••• Shortfin Mako ••••••••••••••••••••

Species: Isurus oxyrinchus (Rafinesque, 1810); from the Greek word isurus (equal and tail) and the Greek word oxyinchus (sharp snout). Class Chondrichthyes, Subclass Elasmobranchii, Superorder Galea, Order Lamniformes, Family Lamnidae—Mackerel sharks.

Species: Isurus oxyrinchus (Rafinesque, 1810); from the Greek word isurus (equal and tail) and the Greek word oxyinchus (sharp snout). Class Chondrichthyes, Subclass Elasmobranchii, Superorder Galea, Order Lamniformes, Family Lamnidae—Mackerel sharks.

Alternate Names: Mako is the work used by the Maori in New Zealand to describe sharks, but this is another shark with many names. In California it’s often called bonito shark, mackerel shark, or simply mako. Also called blue pointer, bue dynamite paloma, spriglio, sharp-nosed shark, pointed-nose shark, and snapper shark (Australia). Called Tiburón marrajo, in Mexico.

Identification: Body more slender than great white. A long, conical-shaped snout with the 1st dorsal fin beginning or slightly behind the rear corner of the long pectoral fin; 2nd dorsal fin small, beginning slightly ahead of the anal fin. A prominent keel on the sides of the caudal peduncle extending from the tail to a point above the pelvic fins. Dark gray or metallic-blue above and on the sides (fading to gray after death), white below. Has a black spot at the base of the pectoral fin. Fang-like, non-serrated teeth.

Size: To 13 feet and over 1,530 pounds; a mako caught by commercial fishermen in Massachusetts in 1997 weighed 1,530 pounds—after being gutted. Most makos seen in California are 6-8 feet long.

Size: To 13 feet and over 1,530 pounds; a mako caught by commercial fishermen in Massachusetts in 1997 weighed 1,530 pounds—after being gutted. Most makos seen in California are 6-8 feet long.

Range: Gulf of California to Columbia River, Oregon but rare north of Point Conception.

Habitat: Epipelagic, aka sunlit or euphotic zone, the top layer of the ocean zones. Typically found in the open ocean, from the surface down to 492 feet, but will also occasionally venture inshore. Eats pelagic schooling species such as mackerel and sardines but also will eat squid, other sharks, dolphin, and even billfish; mako are considered apex predators.

Piers: Uncommonly seen at piers but several have been reported from Santa Monica Bay piers—Hermosa Beach Pier, Manhattan Beach Pier, Venice Pier and the Santa Monica Pier. Makos have also been reported from the San Clemente Pier and Belmont Pier.

Bait and Tackle: Taken on live bait, especially live mackerel. Will also hit trolled mackerel and lures. Usually taken in deeper water with hooks size 6/0-10/0. Makos are the fastest swimming sharks reaching a sustained swimming speed exceeding 22 mph and spurts of nearly 50 mph. They are considered a top sportfish often leaping like a billfish when hooked.

Food Value: Good eating. According to Raymond Cannon in his excellent book How to Fish the Pacific Coast, “thousands of pounds of bonito shark were sold during the meat scarcity in city markets and served in restaurants as ‘swordfish’ and ‘sea bass’ at fresh-fish prices.”

Comments: Richard Ellis in his excellent book, The Book of Sharks, writes, “The mako is the quintessential shark. It is probably the most graceful of all sharks, the most beautifully proportioned, the fastest, the most strikingly colored, the most spectacular game fish, and one of the meanest-looking animals on earth.”

Comments: Richard Ellis in his excellent book, The Book of Sharks, writes, “The mako is the quintessential shark. It is probably the most graceful of all sharks, the most beautifully proportioned, the fastest, the most strikingly colored, the most spectacular game fish, and one of the meanest-looking animals on earth.”